Bruce Bueno de Mesquita is a political scientist specializing in game theory and coalitions. Unlike most academics, he's made a business out it. He routinely consults for the government and businesses trying to predict future political events. He's got a new book out -- The Predictioneer's Game -- which I suspect may be the next Freakonomics. Controversial, widely read, simultaneously powerful and a little gimmicky.

I've discovered that BDM is a polarizing figure among game theorists. On the one hand, he's clearly good at what he does, and he's succeeded in bringing some popular attention to it. On the other hand, he sometimes comes off as arrogant, and he makes some really big claims. Lots of people think that one of these days, he's going to be wrong about something big. I get the impression that a jealous few would like to see it happen.

A bunch of fun links to BDM-related material:

* His interview on the Daily Show on Monday of this week. In my opinion, Stewart asks good questions, but lets him off easy on the answers.

* The TED talk where he first (?) made his prediction that Iran will not get the bomb.

* A really good NYTimes article on the topic.

There's one link I couldn't find: video from the History Channel's show "The Next Nostrademus." I'm told it's over the top. Links anyone?

Politics, lifehacking, data mining, and a dash of the scientific method from an up-and-coming policy wonk.

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Follow up: Big stories from the '08 election

About a month ago, I posted asking for your thoughts on the biggest stories of the 2008 presidential election. If you recall, my goal was to compare your intuition with a computer algorithm chewing through reams of newspaper archives.

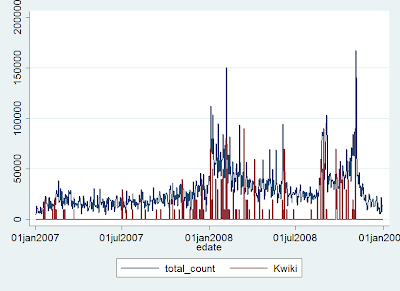

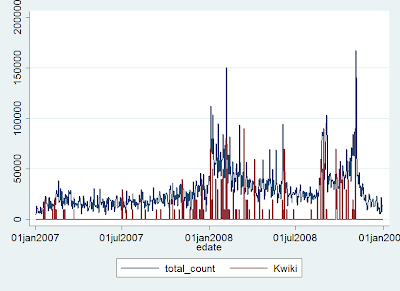

Here are the results, as a line graph. The red line is an aggregate tally of your responses. The blue line tracks total words of coverage devoted to the campaign. The two track reasonably well, taking into account the fact that news coverage often lagged actual events by a day. (I used newspaper coverage for this tally; presumably, evening TV coverage wouldn't have had this lag.)

When you chalk up the important stories, here's what you get. These are the top 10 stories from the election, tallied using three slightly different measures.

Your Responses

1. Reverend Wright controversy

2. Rep. convention; Palin joins ticket

3. Election day

4. Super Tuesday

5. Clinton concedes Dem. nomination to Obama

6. Iowa caucus

7. McCain suspends his campaign to work on the financial crisis

8. Obama makes his “PA bitter” comment

9. Dems vote to seat MI and FL delegates

10. Dem. convention

Computer version A (text volume)

1. Election day

2. Super Tuesday

3. Election week

4. Iowa caucus

5. NV and SC caucuses

6. Obama becomes presumptive Dem. nominee

7. McCain becomes presumptive Rep. nominee

8. Rep. convention; Palin joins ticket

9. Giuliani and Edwards withdraw

10. Dem. convention

Computer version B (IEM trading volume)

1. Election day

2. Rep. convention; Palin joins ticket

3. Final phase of the election

4. Election week

5. WA, D.C., MD, VA primaries

6. McCain becomes presumptive Rep. nominee

7. Super Tuesday

8. Democratic convention

9. NC and IN primaries

10. OR and KY primaries

What you see is that the computer gets a lot of things right (election day, Super Tuesday, the party conventions), but misses nuances that a lot of people thought were important. For example, the Rev. Wright controversy was the number one story in your responses -- almost everyone remembered it as a pivotal event in the campaign -- but it didn't generate that much media coverage, so the computer didn't see it as particularly important. I think it's an open question whether our memories are cloudy, or the computer's event detection is flawed.

If you're really into this stuff, here's a link to the paper. It's half baked, but feedback from the conference convinced me that the concept is worth pursuing as a research topic. Thanks again for your help!

Here are the results, as a line graph. The red line is an aggregate tally of your responses. The blue line tracks total words of coverage devoted to the campaign. The two track reasonably well, taking into account the fact that news coverage often lagged actual events by a day. (I used newspaper coverage for this tally; presumably, evening TV coverage wouldn't have had this lag.)

When you chalk up the important stories, here's what you get. These are the top 10 stories from the election, tallied using three slightly different measures.

Your Responses

1. Reverend Wright controversy

2. Rep. convention; Palin joins ticket

3. Election day

4. Super Tuesday

5. Clinton concedes Dem. nomination to Obama

6. Iowa caucus

7. McCain suspends his campaign to work on the financial crisis

8. Obama makes his “PA bitter” comment

9. Dems vote to seat MI and FL delegates

10. Dem. convention

Computer version A (text volume)

1. Election day

2. Super Tuesday

3. Election week

4. Iowa caucus

5. NV and SC caucuses

6. Obama becomes presumptive Dem. nominee

7. McCain becomes presumptive Rep. nominee

8. Rep. convention; Palin joins ticket

9. Giuliani and Edwards withdraw

10. Dem. convention

Computer version B (IEM trading volume)

1. Election day

2. Rep. convention; Palin joins ticket

3. Final phase of the election

4. Election week

5. WA, D.C., MD, VA primaries

6. McCain becomes presumptive Rep. nominee

7. Super Tuesday

8. Democratic convention

9. NC and IN primaries

10. OR and KY primaries

What you see is that the computer gets a lot of things right (election day, Super Tuesday, the party conventions), but misses nuances that a lot of people thought were important. For example, the Rev. Wright controversy was the number one story in your responses -- almost everyone remembered it as a pivotal event in the campaign -- but it didn't generate that much media coverage, so the computer didn't see it as particularly important. I think it's an open question whether our memories are cloudy, or the computer's event detection is flawed.

If you're really into this stuff, here's a link to the paper. It's half baked, but feedback from the conference convinced me that the concept is worth pursuing as a research topic. Thanks again for your help!

Thursday, August 13, 2009

On putting faith in models

Here's a conversation I had with my brother via g-chat the other day. It's a great prototype of a conversation I've had many times in the last few months. The basic question is "how much faith can we place in mathematical models?" Most people seem skeptical; I'm more of a believer.

This particular exchange was unusual because 1) it was conveniently recorded, and 2) it went in some interesting and productive directions at the end. I'm posting it unedited, except for some spelling fixes and external links. Comments welcome.

This particular exchange was unusual because 1) it was conveniently recorded, and 2) it went in some interesting and productive directions at the end. I'm posting it unedited, except for some spelling fixes and external links. Comments welcome.

10:44 AM Sam: this is probably trivial compared to the analysis you usually look at, but i thought you might like it nonetheless

me: I'll check it out

| 6 minutes |

10:51 AM me: Interesting stuff

I hadn't seen the wine article before

10:52 AM I'd read the paper on war, but I hadn't seen the TED talk

10:54 AM This is exactly the kind of stuff I'm interested in doing

Sam: have you read when genius failed?

me: no

Sam: i can't remember if we talked about it already

it's about a hedgefund

10:55 AM and their story

it's the classic cautionary tale of putting too much faith in models

me: oh, yes

I haven't read it, but I know the gist

10:56 AM I would change the interpretation a little bit and say putting too much faith in a theory.

A model is a theory that happens to be expressed mathematically

Like any theory, if your assumptions are bad your conclusions will be bad

10:57 AM Sam: it was all mathematical

they determined 'actual' risk spreads based on reams of historical data and market conditions

10:58 AM and then tried to beat the market by playing the spreads dictated by their systems

me: right

as I understand it, the mistake they made was in the way they calculated risk

10:59 AM Sam: this is an interesting meta-argument

because you're pointing to the specific problem of their models

where i'm saying their mistake was over reliance on models

me: yes

11:00 AM this is a live debate in social science

I'm a pretty strong advocate for the quant side

11:01 AM Sam: hm

me: I'd say the key question is "is there anything substantively different about theories expressed in math verses theories expressed in English?"

Sam: this is probably a classic

me: classic?

11:02 AM Sam: academics vs business

11:03 AM me: hm

maybe

it's not so clean cut, though, because there are academics who reject the quant stuff and businessmen who embrace it

11:04 AM I think it has to do with the way people think about math

Is it a set of fixed processes for getting answers, or is it a language for expressing ideas?

11:05 AM If it's a language, then the fault for bad models lies is the assumptions expressed, not the language for expressing them.

| 5 minutes |

11:10 AM Sam: accepting that an omniscient agent could express all ideas as formulas and believing that you can are different, right?

11:11 AM its that leap where you decide to stake a business and millions of dollars on the formula that puts you on one side of the line or the other, in my opinion

me: yes, fair points

11:13 AM It seems to me that you're introducing another aspect of theories, which is that they don't just have to expressed, they also have to be acted upon

and strange things can happen when you act on a theory without fully understanding it

It's kind of a Jurassic Park idea

11:14 AM Sam: ha

i guess ultimately the moral to when genius is the same as jurassic park

11:15 AM but trust funds drying up is less dramatic than dino-carnage

me: so maybe the problem with models isn't that they are more likely to be wrong, but that they invite careless extrapolation

Sam: i don't think it's careless

it's hubris

me: "I'm going to leverage a billion dollars 30 times"

11:16 AM "I'm going to bring back dinosaurs from the dead, focusing mainly on intelligent top predators"

Sam: it's the opposite of being careless- it's spending so much time working on a model that you believe that you can and have thought of everything

11:17 AM its validating that model again and again against the datasets you have without allowing for future events to be unknowable

11:18 AM me: I agree -- my only reservation would be that hubris is not specific to people who frame their models using math

Sam: of course

the opposite story is much more common

which is why when genius failed is a story worth telling

11:19 AM when hubris failed would be too common

11:21 AM me: so instead of "people fail because of math," it's "even people using math can fail because of hubris"

11:22 AM Sam: yeah, that's the gist

me: okay, I don't have to feel so defensive now

11:23 AM a lot of the people around me here are model-builders

some of the faculty are among the best in the world

I see both types

11:24 AM Some use models for the sake of transparency -- all the assumptions are laid out for criticism and improvement

Others use models for the sake of beating up on people who don't speak game theory

11:25 AM I'm pretty invested in the notion that models can help the process of collective learning, and it frustrates me when the arrogant ones give modeling a bad name

Thursday, August 6, 2009

Big news stories in the 2008 elections -- Looking for you input

I have a ~10 minute favor to ask. It has to do with timelines again*.

I've pulled a list of the top ~200 events from the run-up to last year's presidential elections. (Download it here as an .xlsx file, here as an .xls file, and here as a .txt file) Sometime when you weren't doing anything anyway (e.g. facebook), skim through the list and pick the top 20 or so events that you think were the biggest stories* in the campaign. If there are important stories that you think are missing, you can add them.

When you're done, post your results in the comments section. Here are the rules:

Like I said, this should only take about 10 minutes or so. Thanks for being part of a convenience sample of the willing!

Some background:

I'm working on a research project using automated content analysis to identify big news stories in archives of media content. The 2008 presidential election is my test case. Basically, I'm throwing a lot of text at the computer and using tricks from computational linguistics to tease out the news stories. It would be neat to be able to do this because 1) news stories are a big part of the way we think about politics, 2) this would make it possible to identify news stories in a replicable way on a grand scale, and 3) complicated algorithms are cool.

Your answers will help me construct a baseline to check how well the algorithm is doing. If the computer finds events that are broadly consistent with human intuition, that's a good sign that it's working. Thanks again for your help.

*PS on my previous post: Chronologic turned out harder than I initially thought! I'm working on ways to weed out some of the ridiculously obscure cards.)

I've pulled a list of the top ~200 events from the run-up to last year's presidential elections. (Download it here as an .xlsx file, here as an .xls file, and here as a .txt file) Sometime when you weren't doing anything anyway (e.g. facebook), skim through the list and pick the top 20 or so events that you think were the biggest stories* in the campaign. If there are important stories that you think are missing, you can add them.

When you're done, post your results in the comments section. Here are the rules:

- By "big news stories," I mean events that did at least one of three things: 1) generated a lot of media buzz, 2) affected public opinion, or 3) evoked a strong response from the campaigns themselves. Any combination of these things qualifies as a news story.

- Don't do any background research and don't ask anybody else for their opinion. I'm just looking for a gut check on which events were the most important.

- Don't worry if you aren't a big-time pundit. I'm not either, and they're mostly bluffing anyway.

- And don't don't don't read other peoples' responses before you post your own -- this will be much more useful and interesting if everyone's ideas are independent.

Like I said, this should only take about 10 minutes or so. Thanks for being part of a convenience sample of the willing!

Some background:

I'm working on a research project using automated content analysis to identify big news stories in archives of media content. The 2008 presidential election is my test case. Basically, I'm throwing a lot of text at the computer and using tricks from computational linguistics to tease out the news stories. It would be neat to be able to do this because 1) news stories are a big part of the way we think about politics, 2) this would make it possible to identify news stories in a replicable way on a grand scale, and 3) complicated algorithms are cool.

Your answers will help me construct a baseline to check how well the algorithm is doing. If the computer finds events that are broadly consistent with human intuition, that's a good sign that it's working. Thanks again for your help.

*PS on my previous post: Chronologic turned out harder than I initially thought! I'm working on ways to weed out some of the ridiculously obscure cards.)

Friday, July 24, 2009

Playtesters needed for a new and improved trivia game

Playing trivia games has always reminded me of listening to a badly scratched CD, or the worst parts of taking the SAT. All three experiences serve up lots of disconnected fragments of something that ought to be big and meaningful, but ends up just coming across as frustrating. Trivia games are history at its reductionist, one-fact-after-another worst.

There are two main symptoms of this fragmentation. First, for any given question, you either know the answer or you don't. Who was Speaker of the House in 1810? Beats me. And if you don't know, there's nothing else to discuss. You bubble in your guess and move on.

Second, there's no element of collaboration or coordination within teams. Trivia teams don't really work together. You just hope your teammates know the stuff that you don't. Practically speaking, this means that most players are not participating most of the time during most trivia games.

Onwards and Upwards

So instead of just griping, I decided to strike back at bad trivia games and do something about it.

I started by writing a web spider to crawl over wikipedia's list of historical anniversaries and pull out dates and descriptions for events in history. For example, according to wikipedia, on May 10, 1801, "the Barbary pirates of Tripoli declare[d] war on the United States of America."

I cached about 15,000 such events in an xml document. Next, I did some text processing to clean up unecessary tags, links, etc. and used XSL-FO scripting to format the events as printable cards. This is all technobabble -- I just want you to appreciate how hard/nifty it all was.

The upshot is that I've created a deck of random historical events, suitable for playing trivia games. They range from the well-known (July 4, 1776 -American Revolution: The Declaration of Independence is adopted by the Second Contintental Congress) to the hopelessly obscure (Nov. 14, 1923 - Kentaro Suzuki completes his ascent of Mount Iizuna). The cards are in .pdf format -- just print and cut along the dotted lines. Depending on your printer, you might want the .pdfs with separate fronts and backs, or you might want the every-other-page version.

Of course, cards alone do not make the game. Here's my attempt to improve on the obnoxious fragmentation of trivia games. The rules are based loosely on an older game called Chronology, but trust me, they're an improvement. I call the new game Chronologic.

Chronologic Rules:

Object: As a team, score the most points by placing events from history in sequence.

Setup: Divide into teams. A few (2-5) teams of a few (1-4) players are good. Choose a target score -- the score where the game will end. For me, 100 is a good target for a ~30 minute game. Decide on handicaps and time limits if necessary. Place the event cards text-side up somewhere where they are easy to get at.

Game play: Play proceeds in rounds. In each round, each team constructs and scores its own timeline.

Building timelines: During each round, your team will construct a timeline by drawing event cards and placing them in sequence one at a time, until you decide to pass. Don't look at the backs of any of the cards until you move to the socring phase! The first event is easy to place in sequence -- there are no other events, so you get it right by default. For every subsequent event, you must decide exactly where it falls in the sequence of events already on the table. If your team doesn't know and doesn't want to guess where a given event belongs, you can pass. Once you pass, you are done for the round.

Every team constructs its own timeline, but they do so simultaneously. So all teams draw their first card together. Once those cards are played, they draw their second cards at the same time, and so on. If your team has already passed during a given round, wait for the other teams to finish their timelines. When all teams have passed, proceed to scoring.

Scoring timelines: Once you finish building your timeline, you get to score it. Timelines are an all-or-nothing proposition. If all of the events in your timeline are in order, your team scores the number of events in the line, squared. If a single event is out of order, your team gets 0 points. So if you have 3 events all in order, you score 9 points. If you have 4 events all in order, you score 16. If you have 4 events but one of them is out of order, you score 0. If you're having trouble remembering your square numbers, they go 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81, 100, and up from there.

After scoring the timeline, add each team's points to their running total. Discard all the cards in all of the timelines. Move on to the next round.

The last round: Once a team reaches the target score, the game goes into a final round. Every team except the one that reached the target gets one last chance to score some points. The team with the most points after the final round wins.

That's all, except for the obvious: discussion, synthesizing sidetracks, and fact-finding trips to wikipedia in the course of the game (after timelines are scored) are encouraged. The whole point is to make sense of how things connect.

I've had a lot of fun getting this game ready for play testing. I'm hoping you'll enjoy it, and I'm open to feedback and suggestions for improvements, extensions, and whatnot.

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

A political puzzle...

Following a hunch, I pulled together historical data on US political participation. Here's the result:

The turnout data is from data is from wikipedia. Non-presidential election years are averages for the previous and following election. Polarization data comes from the difference between House party medians in the first two DW-NOMINATE dimensions. Basically, polarization measures how much Representatives' votes broke along party lines.

Here's the puzzle: up until around 1900, the two lines track quite closely. The raw values are about the same, and they tend to move up and down together. But after 1920, the polarization and participation stop tracking each other. Why?

The turnout data is from data is from wikipedia. Non-presidential election years are averages for the previous and following election. Polarization data comes from the difference between House party medians in the first two DW-NOMINATE dimensions. Basically, polarization measures how much Representatives' votes broke along party lines.

Here's the puzzle: up until around 1900, the two lines track quite closely. The raw values are about the same, and they tend to move up and down together. But after 1920, the polarization and participation stop tracking each other. Why?

Saturday, March 21, 2009

Tracking campaign contributions

Here's a site trying to make campaign contributions more transparent:

"MAPLight.org, a groundbreaking public database, illuminates the connection between campaign donations and legislative votes in unprecedented ways. Elected officials collect large sums of money to run their campaigns, and they often pay back campaign contributors with special access and favorable laws. This common practice is contrary to the public interest, yet legal. MAPLight.org makes money/vote connections transparent, to help citizens hold their legislators accountable."I haven't dug into the site in much detail, but it looks interesting. Anybody know more?

Thursday, January 8, 2009

Following Obama's Inauguration

As much as I'd like to be there, it looks like I'm not going to make Obama's inauguration. D.C. is just too much of a drive. If you're in the same boat, you might want to check out linklive.org. It's a site with video, blog, etc. coverage of the inauguration, plus a social networking component. (Thanks for the link, Rich!)

Here's a blurb from their About page:

Here's a blurb from their About page:

The LINK-live Presidential Inaugural Event ... will connect hundreds of thousands of Americans on the eve of a new era in American politics. Over 4 million Americans will converge on Washington, D.C. to participate in the Inauguration - LINK-live will make it possible for many others in local communities and around the world to also participate in the historic celebration through online technologies.For obvious reasons, the site is targeting a mostly-left-leaning audience, but other than the focus on the Obama administration, I don't see much of an editorial slant. My deeply Republican friends may be turned off by the calls for mobilization/activism that hover around the page, but on the whole it looks like a good substitute for the long drive to the capitol.

Wednesday, January 7, 2009

Wiki-6-D Challenge: "John Wilkes Booth" to "Zordon"

I'm going to relay a challenge issued to me by my brother this morning. Can you start wikipedia's article on John Wilkes Booth and get to the article on Zordon (the disembodied floating mentor of the power rangers) in less than six clicks?

Post your answers. Your linked path must stay within wikipedia without taking shortcuts through index pages. The first person to post the shortest path wins five points, redeemable for swag and glory at the company store. Discretionary bonus points may be awarded for style.

PS. Here's a five-step route to make the return trip from Zordon to Booth. Note that since many wikipedia links are one-way streets, so this path isn't much help going the other direction.

Starting at: Zordon

Post your answers. Your linked path must stay within wikipedia without taking shortcuts through index pages. The first person to post the shortest path wins five points, redeemable for swag and glory at the company store. Discretionary bonus points may be awarded for style.

PS. Here's a five-step route to make the return trip from Zordon to Booth. Note that since many wikipedia links are one-way streets, so this path isn't much help going the other direction.

Starting at: Zordon

- Robert L. Manahan

- United States

- American Civil War

- Abraham Lincoln

- John Wilkes Booth.

Friday, January 2, 2009

Sync

Inspired by Team Hedengren, I've decided to post more often on this blog. It makes for a great New Years Resolution, *plus* an excellent way to procrastinate on already overdue term papers. (Don't worry, they're overdue for legitimate reasons.)

Today I want to plug an excellent book I reread over the break: Sync : The Emerging Science of Spontaneous Order. The book starts off with an improbable chapter about fireflies. Evidently, there are places in the world where fireflies spontaneously start to blink in unison every evening. (See blurry youtube video here.) The puzzle: how do all these bugs achieve perfect unison? They don't start of in sync, they're not particularly smart, and they don't share a metronome or a conductor.

Strogatz (the author) goes on to relate how scientists (including himself) have started to crack this problem. He describes the strong similarities among fireflies, human sleep cycles, pacemaker cells in hearts, superconductors, power grids, collapsing bridges, and so on. It turns out that all of these systems are governed by the same kind of spontaneous order. The book is part mystery novel, part math book, all very readable. Definitely worth a visit to the library or bookstore.

(And now I'll head back to my term paper on "Issue-specific part unity.")

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)