Banks, businesses, and credit card users can rest easy: public key encryption is still secure. Mathematicians breathe a sigh of relief: computers aren't going to replace you by churning out brute force proofs. Vinay Deolalikar, a researcher at HP Labs, is claiming that he has verified the most important conjecture in mathematical computer science: P != NP.

Some links, and then onto an explanation of why this is all a big deal.

What's the difference between P and NP?Suppose you have a friend -- a real whiz at math and logic. "I can answer any question you ask*," she promises, "it just might take some time." Before you ask her to solve your sudoku, route the world's airline traffic, or crack your bank's electronic encryption key, it's worth figuring out "Just how long is it going to take?"

For many kinds of problems, the answer depends on how many moving parts there are. To cite a famous example, suppose I'm a

traveling salesman, using planes, trains, and automobiles to get between cities. I have

n cities to visit. What is the fastest route that lets me visit every city?

Intuitively, the more cities there are, the harder this problem is going to be. If

n=1, the answer is trivial. I start in the single city and just stay there -- no travel time. If

n=2, the answer is easy. It's equal to the amount of time between the two cities (or double that, if I'm required to make a round trip.) If

n=3, it starts to get complicated because I have several paths to check. If

n=100, then solving the problem could take a long time. Even your math whiz friend might have to chew on it for a while.

In the world of computer science, P-type problems are the fast, easy, tractable ones. They can be solved in "polynomial time": if the problem has more moving parts, it will take longer to solve, but not a whole lot longer. Mathematically speaking, a problem belongs to complexity class P if you can write a function

f(n) = n^k and prove that a problem with

n elements can be solved in

f(n) operations or less. Constructing proofs of this kind is a big part of what mathematical computer scientists do.

If we could prove that k=3 for the traveling salesman problem -- we can't, by the way -- then we could guarantee that a computer could solve the 100-city problem in 1 million time steps or less. If your math whiz friend uses an Intel chip running millions of operations per second, that doesn't look so bad. For P problems, we can put a bound on running time, and know that as

n increases, the performance bound increases at worst by the exponent

k.

NP-type problems can get harder, because the definition is looser. Instead of requiring your friend to come up with the answer in polynomial time, we only require her to

verify an answer in polynomial time. ("My boss says I should go to Albuquerque, then Boston, then Chicago, then Denver. Is that really the fastest route?" "Hang on. I'll get back to you in

n^k seconds.") If a problem is of type NP, then we can find the right answer using a "brute force," guess-and-check strategy. Unfortunately, as the number of moving parts increases, the number of possible answers explodes, and the the time required to solve the problem can get

a lot longer.

Finding the solution to NP problems when

n is large can take a ridiculously long time. Some NP problems are so computationally intensive that you could take all the computers in the world and multiply their processing power by a billion, run them in parallel for the lifespan of the universe, and still not find the solution. Problems or this type are perfectly solvable, but too complicated to be solved perfectly.

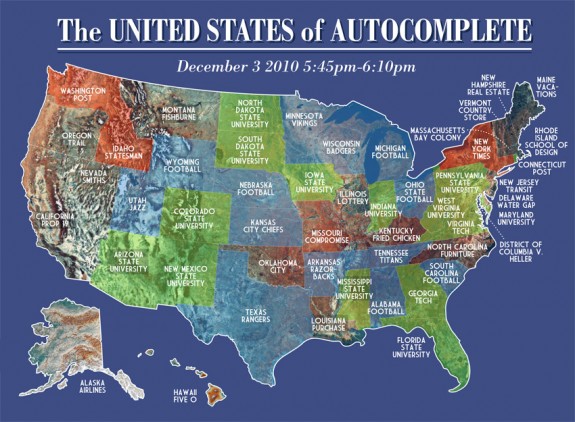

There's a third class of problems, called "NP-hard," that are even worse. Things are bad enough already that I'm not going to get into them here. You may also hear about "NP-complete" problems. These are problems that are both NP and NP-hard. (See this

very helpful Venn diagram from wikipedia.)

The P !=NP Conjecture

The P !=NP ConjectureBut there's an intriguing catch. Until last week, nobody was sure whether any truly NP problems existed.** Maybe, just maybe, some mathematical or computational trick would allow us to convert tricky NP problems into much easier P problems.

Most computer scientists didn't believe that this was possible -- but they weren't sure. Thus, P!=NP was a longstanding conjecture in the field. (By the way, "!=" means "does not equal" in many programming languages). Many proofs had been attempted to show that P=NP, or P!=NP, but all of them had failed. In 2000, the Clay Mathematics Institute posed P!=NP as one of seven of the most important unsolved problems in mathematics. They offered

a million dollar prize for a proof or refutation of the conjecture. The prize has gone unclaimed for a decade.

Last week, Vinay Deolalikar (cautiously) began circulating a 100-page paper claiming to prove that P!=NP. His proof hasn't been published or confirmed yet, but if he's right, he's solved one of the great open problems in mathematics.

So what?Let's assume for the moment that Deolalikar has dotted his i's and crossed his t's. What would a P!=NP proof mean?

One immediate implication is in code-breaking.

Public key encryption -- the basis for most online banking, e-commerce, and secure file transfers -- relies on the assumption that certain mathematical problems are more than P-difficult. Until last week, that was just an assumption. There was always the possibility that someone would crack the P-NP problem and be able to break these codes easily. A P!=NP proof would eliminate that threat. (Other threats to security could still come from number theory or quantum computing.) For wikileaks, credit card companies, and video pirates, this is reason to celebrate.

On the downside, a proof would put a computationally cheap solution to the traveling salesman problem (and every other NP-but-not-P problem) permanently out of reach. This includes a host of practical problems in logistics, engineering, supply chain management, communications, and network theory. Would-be optimizers in those areas will sigh, accept some slack in their systems, and continue looking for "good enough" solutions and heuristics. Expect a little more attention to clever approximations, parallel processing, and statistical approaches to problem solving.

A P!=NP proof can also help explain the messiness and confusion of politics and history.

Recent work in game theory demonstrates that finding stable solutions in strategic interactions with multiple players (e.g. solving a game) is a computationally difficult problem. If it turns out that reaching equilibrium is NP, that would put bounds on the quality of likely policy solutions. For instance, we can pose the problem of writing legislation and building a coalition to ratify it as an optimization problem over policy preferences, constrained by preferences. If finding an optimal solution takes more than polynomial time, all the polling, deliberation, and goodwill in the world might still not be enough to arrive at a perfect (i.e. Nash, and/or Pareto-optimal) solution. In the meantime, politicians will make mistakes, politics will stay messy, and history will stay unpredictable.

Finally, a P!=NP proof puts us in an interesting place philosophically, especially when it comes to understanding intelligence. As with engineering, optimal solutions to many problems will always out of reach for artificial intelligence. Unless computation becomes much cheaper, a computer will never play the perfect game of chess, let alone the perfect game of

go. Other difficult (and perhaps more useful) problems will also stay out of reach.

For those who take a

materialistic view of human intelligence -- that is, your mind/consciousness operates within a brain and body composed of matter -- a P!=NP proof puts the same constraint on

our intelligence. As fancy and impressive as our neural hardware is, it's bound by the laws of physics and therefore the laws of algorithmic computation. If that's true, then there are difficult problems that no amount of information, expertise, or intuition will ever solve.

The jury is still out on Deolalikar's paper. But if he's right, this isn't guesswork or extrapolation -- it's a matter of proof.

* Your friend solves logic puzzles; she's not an oracle. To give you the right answer, she needs to have all the relevant information when she begins, so it's no good asking her to pick winning horses in the Kentucky Derby, or guess how many fingers you're holding up behind your back.

** To be precise here, all P problems are also NP. If I can give you the solution in polynomial time, I can also verify the solution in polynomial time. When I say "truly NP," I mean problems that are NP but not P, such as NP-complete problems. This is the class of problems whose existence has been unclear.